Top 9 Ancient Extreme Sports – So wild they sound made up

Long before modern sports had rules and referees, people across ancient civilizations took part in brutal, bizarre and often deadly games. From wrestling alligators to flipping over live bulls, these extreme pastimes pushed the limits of courage, endurance and insanity. Some were played for honor, others for survival, and a few ended in ritual sacrifice. Here are ten of the wildest historical sports that sound too outrageous to be real, but absolutely were.

Meso-American ballgame

Played across Mesoamerica for more than three millennia, this ancient ball game, known as ōllamaliztli in Nahuatl and pitz in Maya, was far more than a sport. Invented by the Olmecs as early as 1650 BCE, it became a sacred tradition among the Maya, Aztec and other civilizations.

Teams competed on long stone courts, using their hips, arms or even wooden tools to keep a solid rubber ball in play. These balls, made from natural latex and sometimes weighing over 9 pounds, were so dense they could cause internal injuries or even death. In some versions of the game, scoring through a stone ring placed high on the court's wall ended the match instantly, though most games were decided by points. But beyond competition, the sport carried powerful religious meaning. It often served as a proxy for warfare or conflict resolution, and at times ended in human sacrifice.

Archaeological finds, such as ancient rubber balls buried with ceremonial offerings and decapitated player reliefs at El Tajín and Chichen Itza, suggest that losing captains or even entire teams were ritually killed. The Maya myth of the Hero Twins in the Popol Vuh ties the ball game to the underworld, framing it as a cosmic battle between life and death.

Read also: How the 2025 Points System Would Change F1 History

More than 1,300 ballcourts have been found, from southern Nicaragua to Arizona, many located at the heart of sacred cities, where crowds gathered not just to cheer but to witness a ritual performance on a symbolic stage between worlds.

Aligator Wrestling

Long before tourists watched from bleachers, Seminole and Miccosukee men in Florida’s Everglades were wrestling alligators out of necessity.

These massive reptiles were hunted for meat and, later, for their valuable hides, which were traded for supplies at frontier trading posts. Wrestling became a way to capture the creatures safely, and mastering the technique was considered a crucial survival skill.

As tribal councilman Max Osceola once said, “We had to live off whatever Mother Nature provided us.” By the early 20th century, what began as food gathering evolved into performance. Native men showcased their skills at roadside attractions and venues like the St. Augustine Alligator Farm, where taming or “hypnotizing” alligators drew big crowds.

Read also: The 30 Best Players in the Bundesliga right now - Ranked

Wrestling these powerful animals, capable of inflicting serious harm, wasn’t just a show, it was a display of strength, knowledge, and fearlessness rooted in centuries of tradition. Even today, near places like “Alligator Alley,” this dangerous spectacle continues, blending cultural heritage with entertainment.

Chariot Racing

Few spectacles rivalled the chaos and thrill of Roman chariot racing, where four-horse teams tore through vast arenas like the Circus Maximus, sometimes at breakneck speeds.

Originally inspired by Greek funeral games and myths, the sport evolved into a cornerstone of Roman life and politics. At its peak, the Circus Maximus could hold up to 250,000 spectators, all cheering for their faction, Blue, Green, Red or White, each with loyal fans and deadly rivalries.

Drivers were mostly slaves or freedmen who risked death in every race, steering with reins tied around their waists and cutting themselves loose with curved knives if they crashed. The races weren’t just for entertainment, emperors used them to win public favour, and fans used the Hippodrome to voice political dissent, especially in Byzantium, where chariot factions sometimes held real influence.

Read also: From Karting Kings to Mario Kart Masters – How F1 Stars Spent Their Week Off

Some charioteers, like Gaius Appuleius Diocles, became fabulously wealthy, his winnings reportedly totaled over 35 million sesterces. But not everyone was so lucky, as others, like Scorpus, died young in fiery wrecks at the turning post.

Chariot races were intense, often bloody, and always personal. For ancient Romans, it wasn’t just a sport, it was a matter of identity, power, and sometimes, survival.

Jousting left kings dead and dynasties shaken

Jousting may look like medieval pageantry today, but in its heyday it was a brutal contact sport that injured and even killed monarchs. Emerging in the 14th century as a knightly duel, it evolved from cavalry combat into a refined martial game known as a hastilude.

Knights would ride at each other with wooden lances tipped in metal, aiming to shatter them on their opponent’s armor or shield, often with explosive impact. By the late Middle Ages, jousts were governed by strict rules and chivalric codes, yet remained deeply dangerous.

Read also: 23 Favourites to Win the 2025/26 PFA Player of the Year – Ranked

In 1536, King Henry VIII was thrown from his horse during a match, suffering a head injury many believe altered his personality and reign. In 1559, King Henry II of France died when a lance splintered through his visor and into his eye, ending royal jousting in France.

Competitions usually took place in specialized tiltyards, with riders dressed in plate armor weighing up to 110 pounds and riding destriers or chargers outfitted with iron chanfrons to protect their heads.

Some duels went far beyond three lance passes, escalating into full-on weapon exchanges with swords, axes and daggers. These events were part court spectacle, part military training, and fully high-risk theater, attracting enormous audiences from Cambray to Elizabethan London. Over time, as warfare changed, jousting became less about combat and more about ritual and reputatio, until it was eventually replaced by more decorative equestrian displays like the carousel.

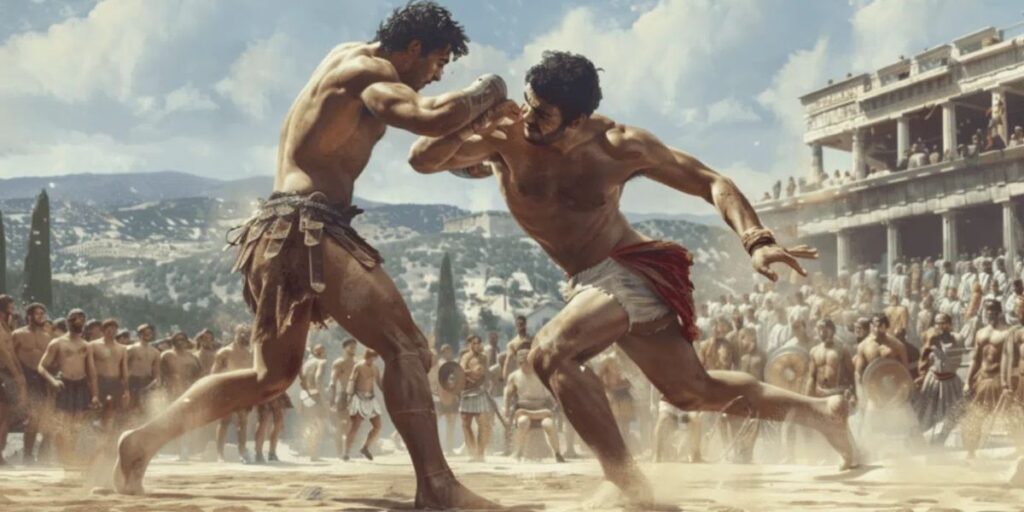

Ancient Greek Pankration

First introduced to the Olympic Games in 648 BC, pankration was an all-in combat sport combining boxing, wrestling, and street-fighting techniques with virtually no limits. Except for eye-gouging and biting, banned everywhere but Sparta, almost anything was allowed, from groin kicks and joint locks to chokes and brutal takedowns.

Read also: Inside Bournemouth's wage structure: Who earns what in 2025?

Fighters competed without weight classes or time limits and bouts typically ended with a submission, unconsciousness or, in some cases, death. Myths credit heroes like Heracles and Theseus with inventing the sport, and it was so revered that Spartans and Macedonian soldiers trained in it, with legends claiming men at Thermopylae fought with their bare hands when their weapons failed.

Among its most celebrated champions was Arrhichion of Phigalia, who posthumously won the Olympic crown after dying in a chokehold while simultaneously breaking his opponent’s toe to force a surrender. Another star was Dioxippus, an Athenian pankratiast who once defeated a fully armed soldier using only a club and his bare hands before being driven to suicide by jealous rivals.

The techniques were as diverse as they were vicious, with ancient artwork showing rear naked chokes, heel hooks, shoulder locks and kicks to the stomach. Training was intense, using leather punching bags, sparring rituals, and strict diets overseen by paedotribae and gymnastae. Over time, pankration’s influence faded under Roman rule, and it was ultimately banned in 393 AD by Emperor Theodosius I along with all other pagan competitions.

But in its time, it was the fiercest contest in the ancient world, forging warriors into legends.

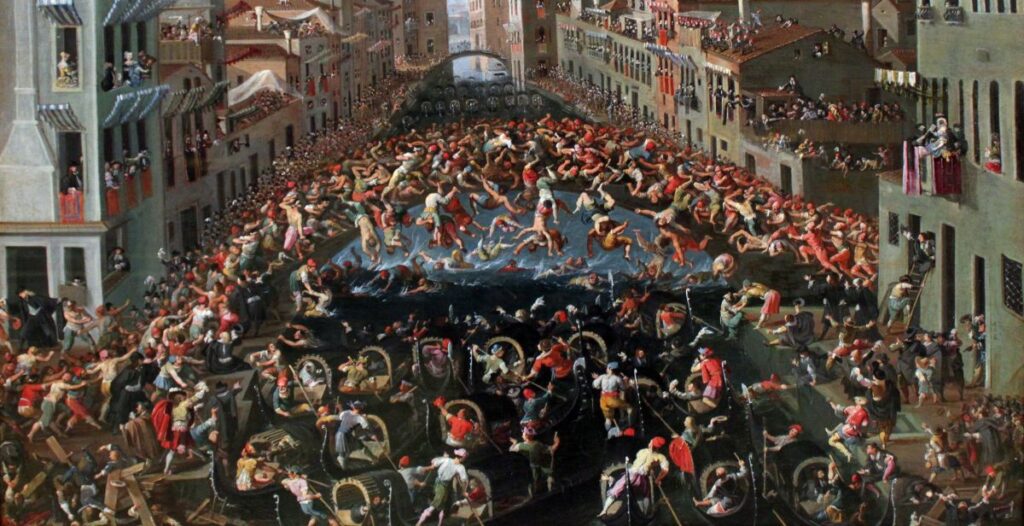

Venetian bridge battles

In medieval Venice, rival factions of working-class men gathered on the city’s bridges not to cross them, but to fight over them. Armed with sticks or bare fists, teams tried to shove each other into the canals below. These mass brawls were so intense that they left participants with broken ribs, knocked-out teeth and smashed jaws. The tradition was so well-known that it impressed foreign dignitaries. King Henry III of France once remarked that the spectacle was too brutal to be a game, but too small to be a war.

Pasuckuakohowog

Played by Algonquin and Powhatan tribes in the 17th century, pasuckuakohowog was less a game and more an organized battle. Its name means “they gather to play ball with the foot” and that's exactly what happened when hundreds, and sometimes even a thousand, warriors stormed a massive playing field, with goals placed nearly a mile apart.

Matches could last for hours, sometimes bleeding into the next day, and were notorious for broken bones, serious injuries, and extreme violence. With no rules to limit physical contact, the game often resembled open warfare, so much so that players wore war paint and ornaments to mask their identities and avoid retaliation.

The ball was crafted from animal hide, and that was the only equipment used. Despite the chaos, the aftermath was almost always a communal celebration, as both sides gathered for a feast once the dust had settled.

According to colonial observers like Roger Williams, pasuckuakohowog was one of the most intense sporting traditions in North America, chaotic, dangerous, and deeply rooted in community ritual.

Bull Leaping (Taurokathapsia)

In the Bronze Age culture of Crete, bull-leaping, called taurokathapsia, was not just a sport but a religious ritual, possibly a rite of passage or sacred performance. Images from the palace at Knossos and elsewhere show male and female athletes performing aerial stunts over charging bulls, either grabbing the horns and somersaulting or leaping cleanly over their backs.

Some scholars suggest the bulls’ sudden neck movements would help launch the leapers skyward. The Minoans depicted these scenes frequently in frescoes, seals, and even ivory figurines, rarely showing bloodshed, which suggests a controlled but dangerous ritual.

The motif spread across the ancient world, appearing in Hittite, Levantine, and even Indus Valley art. A fresco found in Egypt may point to diplomatic or cultural exchanges involving Minoan bull-leaping performers.

Though often seen as symbolic or ceremonial, evidence like the “boxer’s rhyton” hints at real danger, injuries or even deaths may have occurred. Today, similar traditions survive in France as course landaise, in Spain as recortes, and in India’s jallikattu, where humans still leap, dodge, or grapple with bulls in feats of daring deeply rooted in local history.

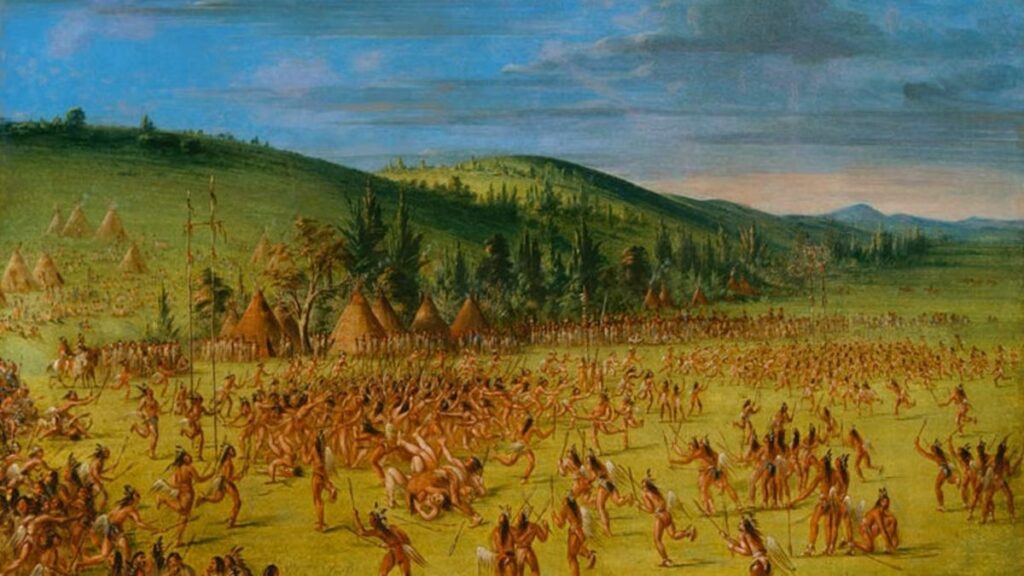

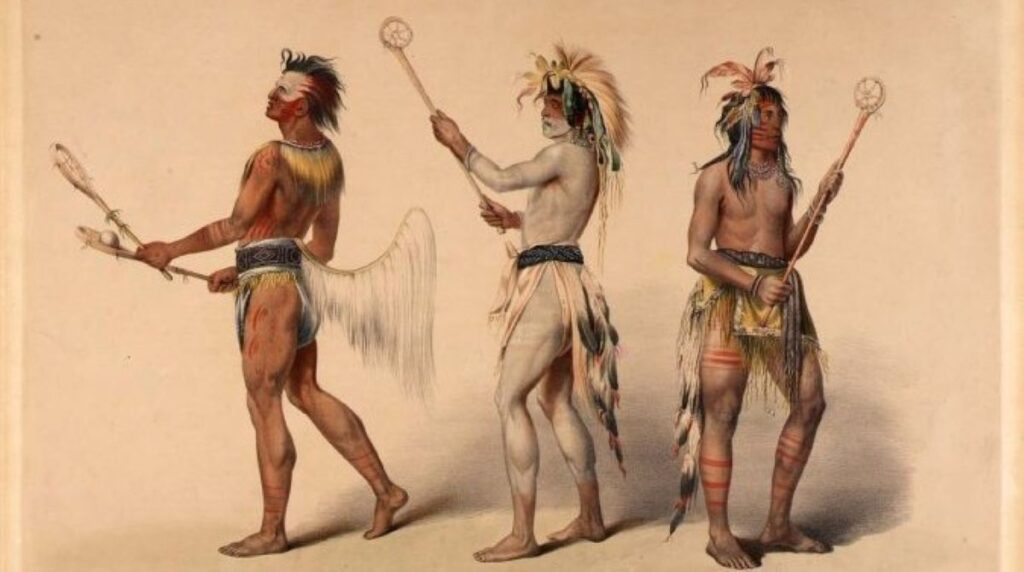

Iroquois and Native American Lecrosse

Long before it evolved into the modern sport of lacrosse, tewaarathon was a physically punishing game played by the Iroquois and other Native American nations to train warriors, resolve disputes, and even offer spiritual prayers to the Creator.

Known as the “little brother of war,” the game involved hundreds of men from opposing villages charging across fields up to six miles long, wielding handmade wooden sticks strung with leather or sinew to catch and carry a deerskin ball. There were no boundaries, no protective gear, and few rules beyond those agreed on just before the match.

Contact was brutal and constant, and passing the ball was considered a trick, honor demanded players face opponents head-on. Games could last from sunrise to sunset over several days, and before each one, teams underwent war-like rituals including ceremonial body paint, songs, sacrifices, and pep talks from medicine men.

Even wagers were common, with players betting items like knives or horses, the spoils displayed near the field. After the final whistle, a feast usually followed, reinforcing the game’s role not just as sport, but as a powerful cultural and spiritual institution.